On the morning of July 5, 2018, a man in his 60s enters the gate of the house at 96 Eroilor Avenue, Voluntari, and is registered as a beneficiary of the social care home for dependent persons that operates here.

On the first night spent here, the man goes out on the second floor balcony of the house and throws himself into the void, smashing himself on the stone slabs of the courtyard.

He dies instantly.

“I wasn’t on duty at the time, it was my other colleague. According to my colleague, he went to the first floor, looked down and said ‘No, it’s too close!’, then he went to the second floor and bent down like this and said ‘Eh, maybe it still works…’,” sighs one of the employees of the social care home at the time. We’ll call her Gina.

“It happened at night, when my colleague was somewhere… you know, she has a little room where she still lives, and that’s probably when (it happened, ed.). In the morning she went in and in the evening she threw herself over the balcony,” says Gina.

She doesn’t know why the man did it. “Maybe he was depressed, or maybe he was angry that whoever brought him there brought him there,” adds Gina, a simple woman in her late thirties without much schooling.

Monday, 20 April 2022, Eroilor Boulevard, Voluntari. Shortly after 9.00, a Logan stops in front of the two-storey house at number 96. Several people get out of the car in a hurry, and the pavement in front of the house comes alive. Shortly afterwards an ambulance appears, then a bus from the Voluntari City Hall, then other cars and ambulances.

Between carpets, furniture and potted plants, which are hastily loaded into several cargo vans, ambulances and the City Hall bus are loaded with people who are visibly suffering. In canes, frames, wheelchairs and stretchers, dozens of people are being taken out of their homes one by one to be moved a few blocks away.

The operation lasts until around 5pm and was filmed with the surveillance cameras of the house at 96 Eroilor, known in the area as the “Gerbera” villa/pension/hotel.

“These are the pictures that show exactly how she set me up and ran away, but she had other things to hide, the money I think was the last problem,” says Marius Sârbu, the owner of the house where until April 20 a mixture of a home for the elderly and a care and assistance social care home for adults with mental disabilities operated by a certain Cristina Maria Dumitra (formerly Văduva, née Mareș) functioned.

Anatomy of a stake

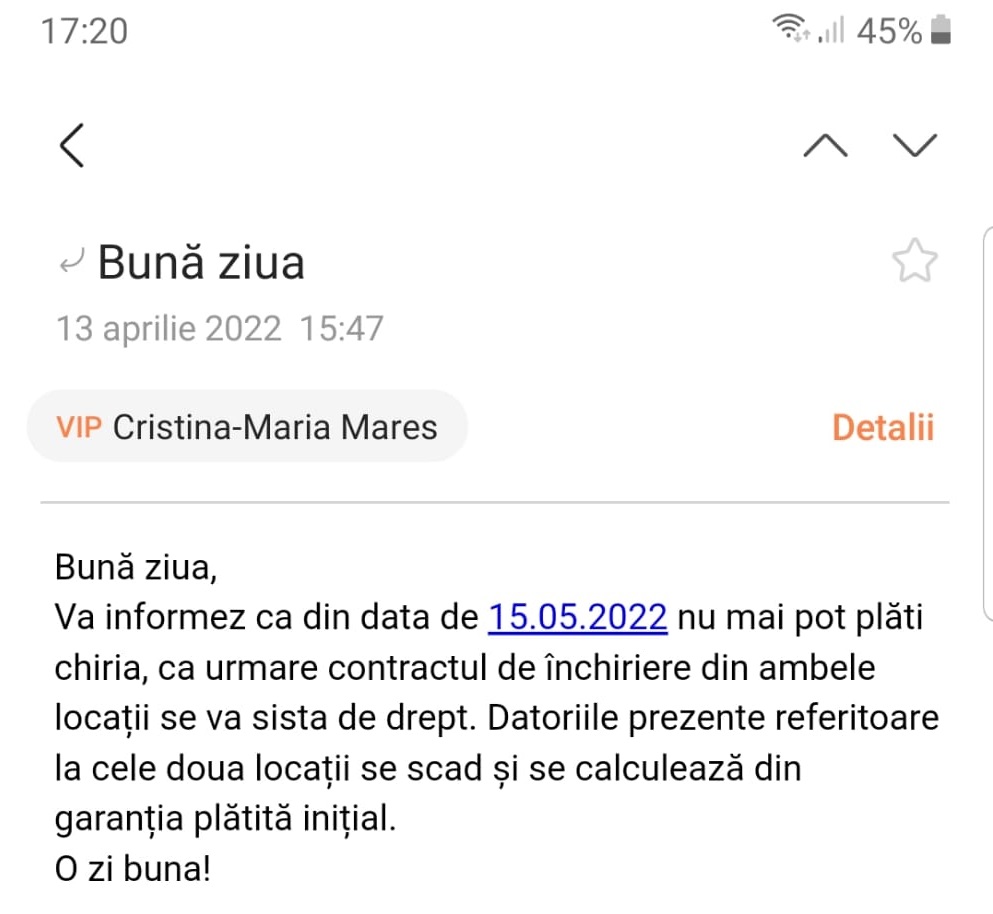

Exactly one week earlier, on 13 April, after several months of not paying either the utility bills or the rent, Dumitra had sent the landlord a telegraphic email informing him that she could no longer pay the rent, so she was terminating the contract as of 15 May.

When she writes “the two locations”, the entrepreneur Dumitra refers both to the Gerbera villa and to another house rented by Dumitra from Sârbu, in Violetelor Street in Ștefăneștii de Jos, where another identical social care home used to operate.

The day after receiving the email, on 14 April, the owner goes to the house in Ștefăneștii de Jos, where he finds the disaster: sick old people kept naked, dirty and uncared for, in beds with traces of faeces.

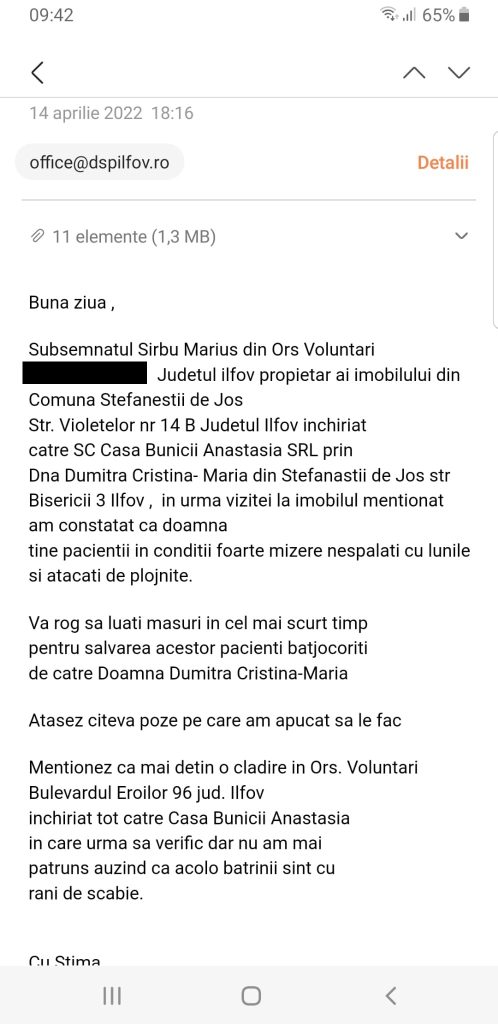

The same day, Sârbu complains to the Ilfov Public Health Directorate and the Ministry of Labour about the degrading treatment of the beneficiaries in the social care home in Ștefănești.

In his complaints to the authorities, he speaks of similar things happening at Gerbera, but claims he refused to go and check there after being warned by one of the staff that the beneficiaries had mange and the house was infested with bedbugs.

Although complaints were filed, absolutely nothing happened, so after a few more days, on 19 April, Sârbu complained about what had happened in his home – turned by Cristina Maria Dumitra into a social care home for vulnerable people – to the Voluntari police.

The next day, on 20 April, the entrepreneur Cristina Maria Dumitra hurriedly moved the beneficiaries and belongings from the Gerbera villa and the other social care home, the one in Ștefănești, combining both businesses in what was to become the “Residential Care and Assistance Centre for Dependent Persons – Casa Cora”. A large new house located a few minutes walk from Gerbera, also in Voluntari, on Camil Petrescu Street at number 5.

This is when the owner Sârbu also enters the Gerbera house and realizes the extent of the disaster.

Beyond photos

Another former employee of Cristina Maria Dumitra told reporters from the Media Investigation Centre (CIM) and Buletin de București how the “clients” of the social care homes became unmentionables within months of crossing their threshold.

We’ll call her Elena. She worked both at the Gerbera social care home and afterwards at Casa Cora, the place where Dumitra has been gathering her businesses.

“There’s nothing right there, believe me. They were all bitten by bedbugs, they ended up with worms in their private areas, scabs deep to the bone, you can’t imagine! On any given day – so any given day! – there wasn’t a day that there weren’t two or three big, nasty, nasty irregularities. You simply can’t have two nurses in the whole asylum, they just can’t cope”, Elena recounts her experience as an employee of the “social services” provided by Cristina Maria Dumitra.

“They had bedbugs on them… God forbid! At Gerbera, yes. Under the bed, if you lifted the mattress, at least in the evening, when it was dark… I taught them psychology, for real! So in the evening, if you lifted the mattress, they would run all over the place, it was… I was really shocked!” the woman continues her story.

Why all the mess?

“Well, here in Casa Cora, where we moved from Gerbera, they had one bathroom on one floor. On the first floor, one bathroom for 27 people,” she replies.

She remembers a horrifying situation: one day she found an elderly beneficiary who had just wet her bed.

“No one wanted to touch it out of disgust, I took it with the sheet. I put her in the bathtub, because there is a bathtub there, in that common bathroom for 27 people…”, Elena describes the context of the photo taken in Casa Cora, in the space where the two social care homes that had functioned in Sârbu’s houses in Voluntari and Ștefănești had just been reunited.

But similar things were happening before she left the Gerbera house.

“They had a room at Gerbera, somewhere down in the basement. When I first arrived I heard ‘ah, you’re going to the ones at the Groapă?’ I was thinking ‘what do you mean at the Groapă?’. And when I got there and saw what it was… so I couldn’t believe it… There was shit on the floor, you were slipping on shit, excuse me for talking like that but that’s how it was! Nobody would go into their living room, there was a smell… They kept the women there mostly locked up,” Elena recalls bitterly.

“Did they have medical assistance?” we ask her.

“No way! I’d call Rescue. I’d tell them, ‘this man has had a fever for three days, right? We have to give him something, we need a doctor’. ‘Call the ambulance!’, they said. ‘Well, what fever are you calling me with, 38 in this man?’, the ambulance people said, and they refused to take him. And then the man died of sepsis. Toma Ion called him. He came to our asylum there, to Camil Petrescu. In the last three months the man died of septicaemia, because I kept barking that he needed medicine, to give us antibiotics… I couldn’t take any more, because I used to take them from the pharmacy…”, the woman recounts one of the horror episodes she experienced.

We insist and ask about the social care home’s contracts with specialist doctors.

“They had. They had this: the cardiologist, who came once a month, every three weeks, and asked each one, with his notebook in front of him, ‘How is this one?’ He didn’t see them, because he was disgusted! He never saw them. The psychologist did come. She’d come and take it through every room, poor woman, she was the only one who took it through every room. There was the internist, who came and sat at the table and wrote sheets and so on. And the psychiatrist, yes, who sat in the heat, did nothing to them,” the woman recounts.

And there would be something for the specialists to see. For example, beaten beneficiaries.

“That’s how I found this lady, she was most likely beaten before I came, I can’t figure it out. The funny thing is that they were saying that everyone, damn it, got hit by something! This old old lady was always comforting me, that I was bringing her food and I was always giving her two portions, I was always doing my best to give her two portions, that I could see she would eat some more, and I found her one day like this”, Elena tells.

“There was another one coming down from above, hungry. He’d run to the kitchen to steal food, they’d catch him and beat him. Another lady, with serious mental problems, would urinate where she saw tiles. And she laughed, because she had a thing about laughing, and one day I went and found her bruised in the eye. So she has a black eye. I asked what happened and the colleagues said ‘I told her to get out of bed and she hit her eye on the edge of the bed’. Oh, fuck… Or the other one, who ‘fell out of bed’. Of course they beat her, you can imagine. The funny thing is, they didn’t beat each other, the sick ones. The nurses beat them!”, Elena continues.

“You could clearly see which ones were beaten, what the hell… Another lady… I found her the same, with a bruise in her eye and forehead. They told me ‘she fell out of bed’, but the woman was paralyzed. To be able to change her you had to turn her over, but I’ll tell you what they did to her: they turned her over like they used to do, ‘go on, do it, fuck off’ and when they picked her up they threw her against the bedside table,” the woman recounts.

“Did these happen at Gerbera or where they are now, at Casa Cora?” we ask, barely hiding our amazement.

“Both in Gerbera and here, at Cora,” Elena answers us immediately.

Food? Nothing, tasteless liquids

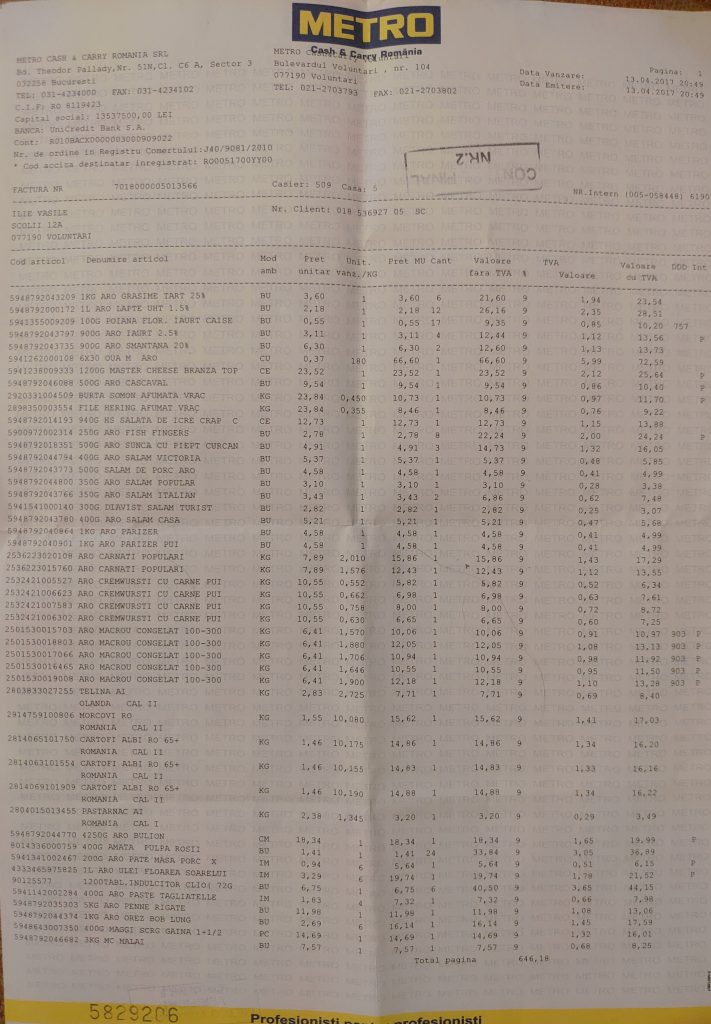

“A dry soup, without taste, without anything, and that one brought from the nurses’ home. A soup of boiling water, a dish of potatoes, mixed with pasta. Whatever you can find. They don’t have snacks, they don’t have a fruit… That’s it,” the woman says.

“Around 8.30 in the morning he would give them – that’s how it was at the time I was there – the cheapest salami, salami from ARO, margarine from ARO. Marmalade, I mean not even a jam, a jam like people…. Many of them didn’t want to eat, because nah, they had been used to something else. So… For lunch, that soup, with the second course, also boring. Or they’d make these… bean pods, always bean pods, beans, and they’d make those too, flat. I used to explain to them ‘don’t give them any more beans because they’re shitting themselves, they’ll spoil their tummies, because we only put junk in them, only crap, that’s the least you can do: don’t make them any more beans!”, Elena recounts.

“To the ones we spoon-fed them or to the very old ones we didn’t put meat at all, we only put it on those who started to scream, to make a fuss. He would make them something out of bones, from their heels, backs, with butts and throats. So they never saw any real meat like that. What else… undernourished. I mean, if you see pictures of how they came and went…”, Elena further shocks us.

How many deaths?

I asked Elena how many beneficiaries died while she worked for Dumitra, both at Gerbera and after the “merger” of the people of Gerbera with those of Stefanesti, apart from the man who jumped from the balcony.

She couldn’t say exactly. In the long discussion with her, she repeatedly stopped sighing and told us about many of those mentioned in the dialogue with us “hope he is still alive!”.

“I wasn’t working there when that man killed himself, I just heard the story. But I caught enough of it myself… One lady, I held her hand for a whole day until she died. Because for three weeks she refused to eat. Another lady (died. n.r.) three days after she came, because she had generalized edema. In her case we expected her to die. Now do you know what happens? It’s normal for people to die in a nursing home, but it’s not normal. It’s normal to die of old age, but not to… every day they were worse!” the woman revolts.

Evidence

Gina and Elena’s former boss, Cristina Maria Dumitra, has been dealing with addicts for 11 years. In all that time she has had, according to the Official Gazette, at least six companies operating in at least as many homes.

In one of them, reporters from the Media Investigation Centre (CIM) and Buletin de București found a clearer answer to the question about the deaths, as well as other undeniable evidence in support of Elena’s claims.

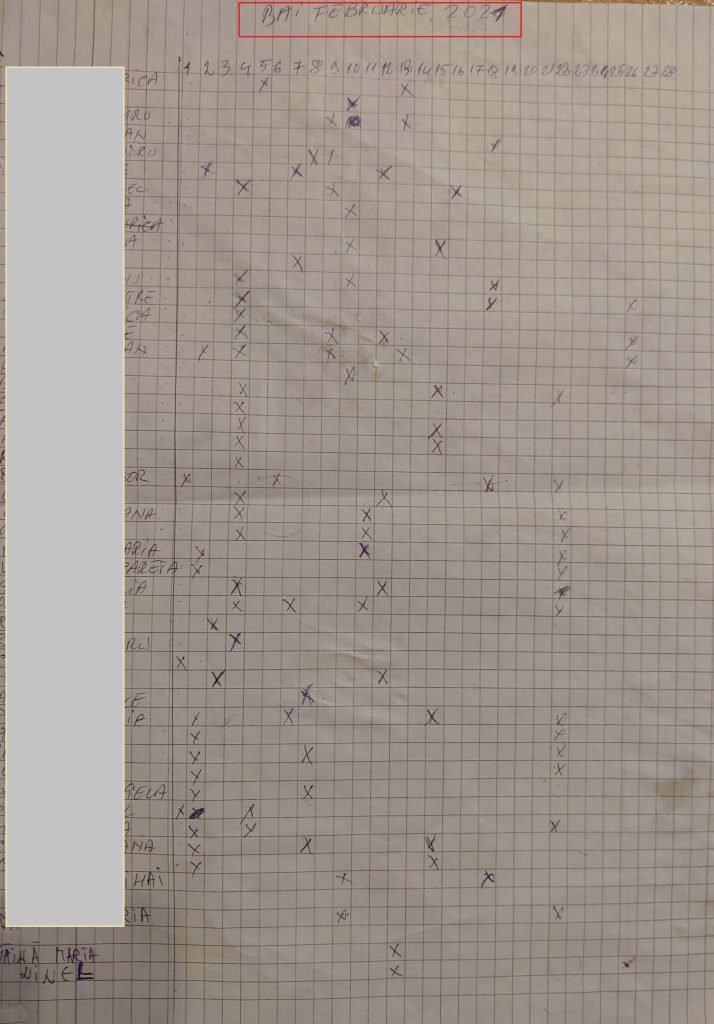

In a pile of rubbish left behind by Cristina Dumitra’s men we found a notebook. Under the green, posh cover it says “Attendance notebook”.

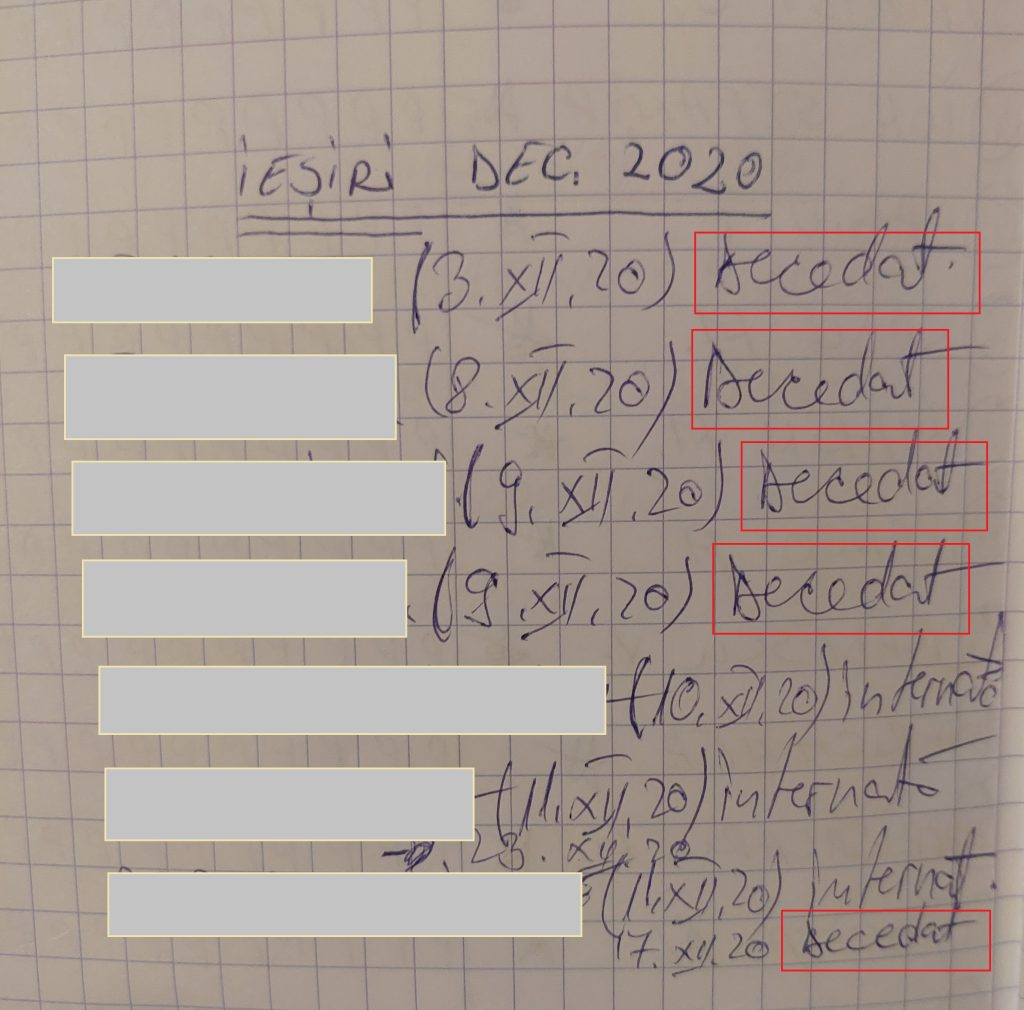

Left behind by Cristina Maria Dumitra’s men, the notebook is revealing of the horrors that took place in the Gerbera house, as it covers that period. We note, for example, that in December 2020 alone, out of a total of 34 beneficiaries, five died. Two others, admitted to hospital in December 2020, died in the first days of the following year, in January 2021.

Although December is the month with the most “discharges”, as deaths (or hospital admissions) are called, the other months listed in the book are not so high either. We counted, in the period February 2020 to March 2021, so one year and two months, a total of 21 deaths.

In another file, entitled deceased, two more people appear, but it is not clear when they died.

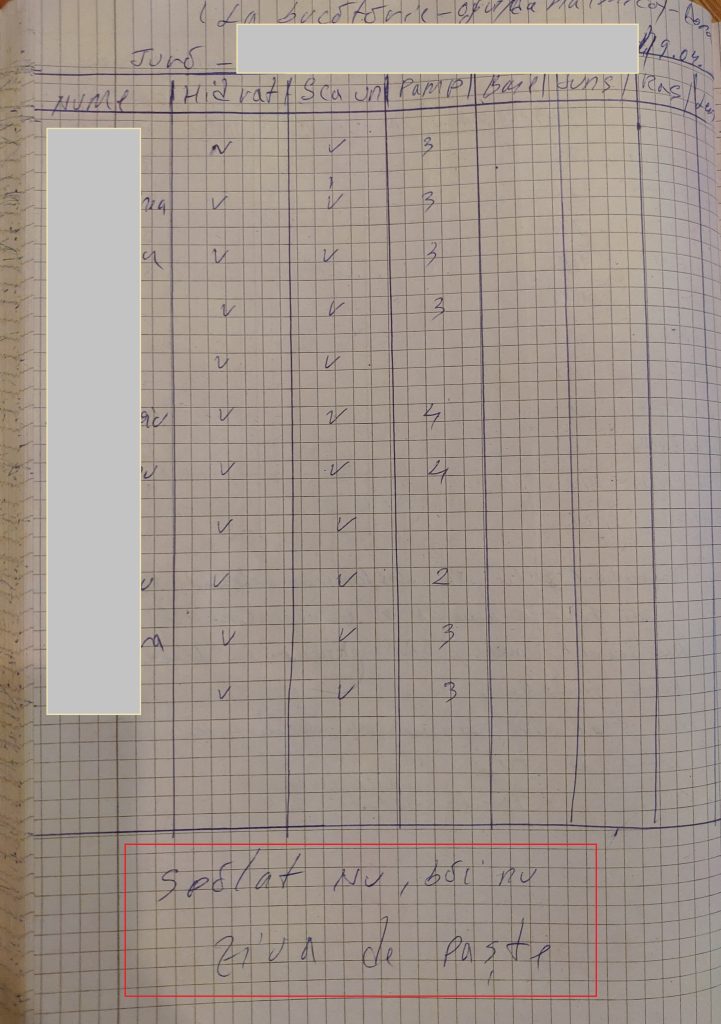

In the same pile of papers left behind by the entrepreneur Dumitra (ex-Mars, ex-Widow) we also find a “statistic” made by her own employees. From it we understand how it was possible for people to live in such misery: many of the beneficiaries took a bath once a month.

On Easter Day 2020, for example, a report on some of the beneficiaries, probably one floor, shows that none of the people had a bath that day.

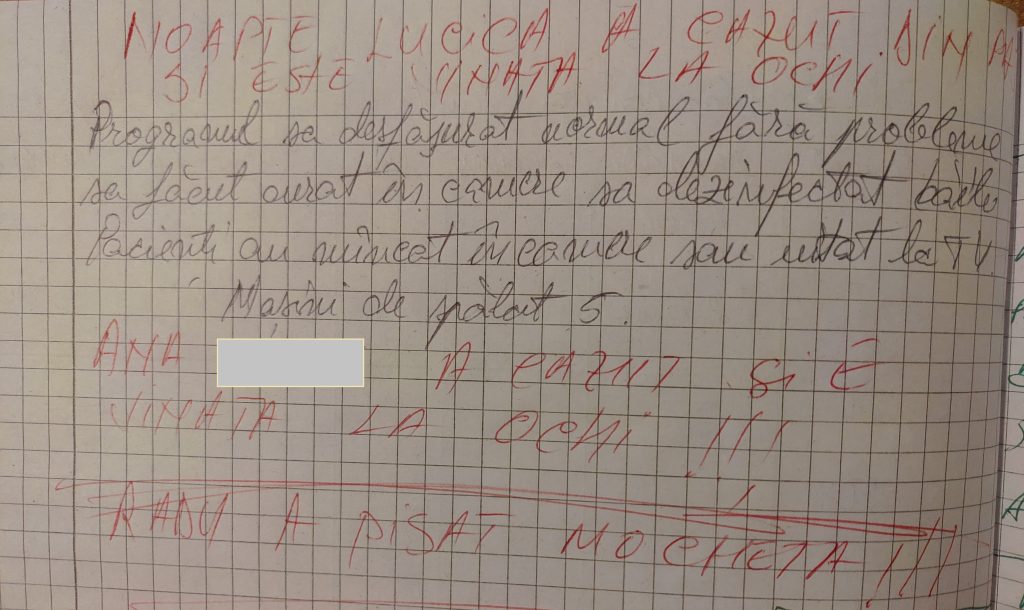

In another document, someone who appears to be the head nurse angrily notes that on the morning of February 8, 2020, when she came to work, she found the recipients dirty, their pampers unchanged, and their clothes soiled with urine and feces.

Several end-of-day reports confirm Elena’s claims about the beatings of the beneficiaries in Cristina Maria Dumitra’s social care home. The documents show how the beneficiaries “hit each other” and had black eyes. On one day, for example, two women “were careless”. Interestingly, the report seems to be made in two stages: at first everything was normal that day, but then someone comes back, in red pen and capital letters, and adds the details.

And the food is where the pile of paperwork clears up: we find an older Metro invoice. From the 2017 document, we are confirmed that, apart from vegetables, absolutely everything bought for the beneficiaries’ meals, at least in 2017, was the cheapest variety of product.

“I should have known!”

Marius Sârbu says he never imagined the situation had become so tragic in his home.

He then remembers that, before running away, with all the people and full of debts, because of complaints made by employees and suppliers to whom he also owed a lot of money, Dumitra changed the rental contracts previously signed with a new company.

“That’s when I should have known something was wrong. I was wrong, especially since I had forgiven her once before. I got over the first sting she gave me, that she had been a tenant here once before, also with a social care home, and she left again without paying me. Then she went somewhere in Afumați…”, Marius Sârbu tells us.

We checked what Sârbu said in official databases. According to the Official Gazette, Dumitra Cristina has run six companies in the last 11 years, either in her name, then Mareș, or in the names of her relatives.

Her business history shows a modus operandi: Cristina Maria Dumitra accumulates debts on one company, then cleans up her past by setting up another, brand-new one. She collects debts again to the state and to suppliers and the new one, then starts again with another firm, in another rented house, and so on.

For 11 years.

The first business on the backs of people who can’t look after themselves started in August 2012, under the name “Maria’s Nursing Home”.

She was 25.

Barely a year passed and Dumitra opened another business, Casa de Odihnă Cristina, this time with her mother, Mareș Florica. The latter, we learn from documents from the Trade Register, was practically an intermediary, as her daughter, Cristina Maria Mareș (now Dumitra), was the one who managed the business.

The first irregularities that reporters were able to document occurred in 2015. The Territorial Labour Inspectorate (ITM) fined the Cristina Rest Home 30,000 lei for having employees working illegally without work permits.

This, however, was to turn out to be a small problem compared to the misfortunes that were to take place in the social care homes of Cristina Maria Dumitra’s companies.

It’s unclear whether problems with the ITM or other debts are catching up with the young businesswoman. What we do know is that she is setting up a new company: the Casa Maria Care and Assistance Centre Ltd.

Soon, Cristina Maria Dumitra’s business ends up in trouble under the new firm as well. Conditions in the home leave much to be desired, and debts pile up. “The nurses are tired, lacking in patience, empathy and from fatigue they even scream, there are girls who even hit them with the sheet wet with their own urine”, someone wrote in a Google review.

Law response

Marius Sârbu, the one “stiffed”, complained everywhere about the precarious conditions in which the beneficiaries were kept. But he started complaining only after he was told he was no longer getting his money, and not a week later the business was moved. By the time the institutions he complained to reacted, it was too late.

Thus, the Ministry of Labour and the Ilfov Public Health Directorate, the first to be notified by Sârbu on 14 April, responded to him after a month and a week and after almost two months respectively.

The complaint left by Sârbu – accompanied by a few photos, not the most harsh ones – at the Ministry of Labour’s registry office on 14 April did not arrive until 19 May at AJPIS Ilfov, the Ilfov branch of the National Agency for Payments and Social Inspection (ANPIS) subordinate to the ministry. The AJPIS Ilfov inspected the new company in vain: the house where Cristina Maria Dumitra had just moved her business still looked good and the conditions were good.

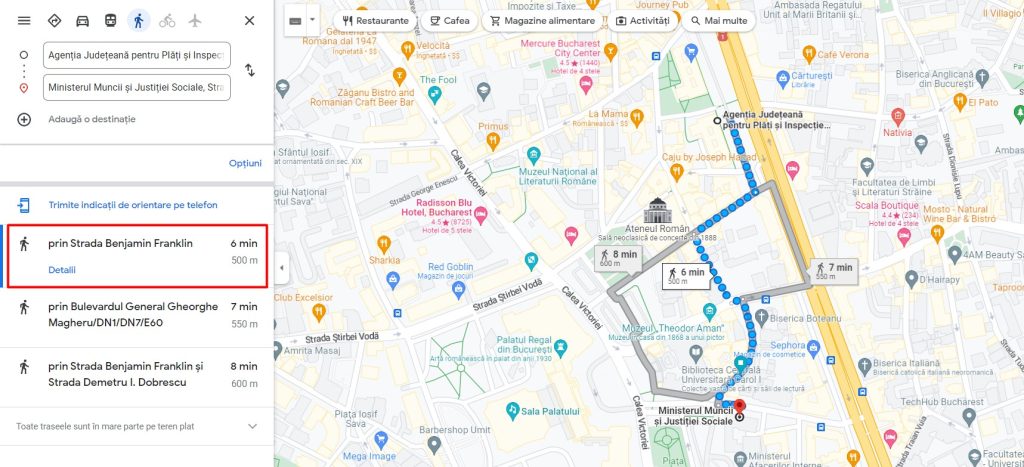

A month and almost a week for a complaint requiring urgent intervention to arrive from Dem I Street. Dobrescu, from the Ministry of Labour, to the AJPIS Ilfov office on Magheru 7. Google Maps tells us the distance is 500 metres. Or six minutes on foot.

The complaint filed by Sârbu with the DSP Ilfov also on April 14 received a response from the institution on June 3, although, according to him, a few days after he sent the complaint by email – with some of the pictures, some of them less harsh – he also went in person to the institution, seeing that nothing was happening. He even went so far as to threaten to notify the press. That’s also when he registered a new petition. After a few more days, exasperated, he filed another.

The first thing Sârbu is told by the officials of DSP Ilfov almost two months after the first urgent petition? That in the houses indicated – i.e. his! – “no more elderly care activities are carried out”.

To the police in Ilfov, the deceived Marius Sârbu went later, on 19 April. The county police redirected his complaint to the Voluntari City Police, where he arrived the next day. In response, however, the complainant Sârbu was answered on 16 May. The Ilfoveni police officers informed him, in their reply, that they had checked the information in his complaint – they did not specify when exactly – and that nothing was confirmed.

Beyond the institutions called upon to intervene, which functioned as best they could, how come no one knew what was going on there? Who should have complained about the conditions in which these people were kept?

The employees? From talking to the two women I called Elena and Gina, but not only to them, those who worked for Cristina Maria Dumitra only came into conflict with her after being “burned” for money. Some of the employees who ended up arguing “over money” with Dumitra’s boss complained about what they saw here, but the institutions either didn’t get to the control before changing their premises, or the information “got” to Dumitra, who prepared and the control turned out well.

Some of the employees tried to put things right as much as possible, but only on their own. One of the employees, for example, even went so far as to tell her boss, at the time of the rift between them – also because of money – that she preferred to donate the money she still had to receive for her work to the social care home’s beneficiaries. “(…) to buy bandages and sponges, individually, for each patient”, according to her.

Those who were paying for the “services” people received here? I mean their families or the state. In recent years, the pandemic has been the perfect reason for the landlady to stop allowing relatives to visit the social care homes.

Outsiders were blind, even those who wanted to bring an elderly person to drop off at the home. “That’s how people used to come, they’d come to the gate, ‘sir, look, we’d like to bring someone here too.’ At Gerbera they wouldn’t let anyone in! ‘ ‘Sir, if you want to bring (someone, ed.) fine, if not, fine again, you don’t come in!’ He would only take those who said ‘OK, here’s the sick man at the door’ and we would come for him,” Elena recounts.

There were exceptions, however.

“Some people would come, but they would say in advance, ‘See we’re coming at this time’ Or, for example, if they came unexpectedly and we woke up with them at the gate, we’d let them go, but we’d say ‘Stay here for five minutes, you’re not allowed to come up, because he’s with COVIDu’, and we’ll call you from the room, give us the number and we’ll go up to the ward and we’ll call you from the room to talk to the person’. And you’d wipe the person a little bit on their face, on their mouth, do their hair a little bit and that was it,” Elena explains.

The Covid-19 ‘scare’ had even come to be invoked at check-ups.

“If you go to the Voluntari town hall and ask how many times they knocked on the Gerbera gate and nobody answered… Not even for the census, because I still answered the gate. The one (with the census, editor’s note) said ‘There are a lot of people with addresses here that we have to register, there’s nothing we can do!’, and I called her (the boss Dumitra, editor’s note) and told her. She said ‘yes, yes, I’ll call’. Now if she called I don’t know, but I don’t think so. They didn’t open the gate, they didn’t open the gate!”, Elena continues.

With the papers in order, Cristina Maria Dumitra receives beneficiaries from families who can no longer or no longer want to take care of them, or from the municipalities of Ilfov.

“She paid the state, through this social insurance, because she was associated with Bălăceanca. They were social cases, nobodies, from the street. Anyway, I think she also benefited from something through the town halls, because I don’t think she kept them for nothing, twenty-something people. In Ștefănești, she was always taking social cases from them at the hospital”, says Gina, who worked for Dumitra for many years, but who doesn’t seem to understand that a state mental hospital cannot become “associated” with a company that operates a social care home for the persons with disabilities or an old people’s home.

Confirmation

At the beginning of September, a team from the Legal Resources Centre (CLR) arrives at “Cora House” for a first unannounced monitoring visit. Cristina Maria Dumitra’s social care home is still new, people have only been here for a few months. However, the irregularities found are major: neither on this first visit, nor on the next two, in October and November, the new company operating the social care home has no more than two employees as nurses. But it does have more than 60 beneficiaries, well over the social care home’s maximum capacity of 48 people.

What is more serious is that, despite the official quality of the CRJ’s staff, as confirmed by the protocols signed with the state authorities, the CRJ’s monitors have not been able to find out from the head of the social care home, the third employee always found there, essential information: exactly how many beneficiaries Casa Cora has and how they got here, through which contracts.

“We were told that we could not have access to this information, as it was with the ‘boss’, most likely the wife of the company’s administrator, Mr Dumitra. Neither the ‘boss’ nor her husband could be reached to find out this essential information to understand what’s really going on here,” Georgiana Pascu, programme manager at CRJ, told reporters.

From discussions with the head of the social care home, CRJ monitors learned that, in addition to those brought here by families, there is a contract concluded by the social care home with the Pantelimon Social Welfare Department and “next” contracts with the County Directorate of Social Care Ilfov (hereinafter called DGASPC Ilfov) and the Voluntari Social Welfare Department.

Reporters asked for information from the two institutions. DGASPC Ilfov officially communicated on December 28, 2022, that it did not have a contract with Cristina Maria Dumitra’s newest company until that moment, and the people of the eternal mayor Pandele registered the request on January 5, but never responded.

The CRJs note, even despite the lack of factual information, that the center is overcrowded and people are rather uncared for. “There is one bathroom on each of the two floors, two bathrooms for over 60 people, totally dependent people. A perfect context for serious hygiene problems,” Pascu continues.

“The smell of urine was present on both floors, in some spaces dirty clothes or used materials were thrown on the floor: pampers, paper, rags,” the CRJs write in their visit report.

Moreover, the beneficiaries looked bad.

“Most of the residents were thin, ‘skin and bones’. The coordinator of the social care home presented the dining room and the kitchen, both located in the basement of the building, but said that, during that period, food is brought by a catering company from Afumați. No contract, no menu for any of the residents, nor whether any of them had intolerances or diagnoses that would justify a special diet, was presented,” the JRC monitors write in the visit report.

So, in the absence of details, it could be any other catering company in Afumați, but it could also be the same story: the non-existent catering of SC Mititei la Tomiță SRL, in fact the “stews” concocted in the kitchen of the “Armonia” social care home of Ștefan Godei and Ligia Gheorghe, people close to the Firea-Pandele couple. We don’t know.

According to the social care home manager, Casa Cora has contracts with all kinds of specialist doctors, but they were nowhere to be found during any of the three visits of the CRJ from September to November 2022. Nor could the beneficiaries the CRJ team spoke to confirm that there was constant medical care for them.

Under the conditions described, dramatic situations obviously arise.

“On the second floor, a resident was living in the hallway. From the information we received from her, she is retired for medical reasons, she was an electrician. She doesn’t know if she has relatives or friends, no one visits her, she doesn’t know if she has any income. She has no personal belongings, no bedside table or wardrobe allocated to her. Her bed is placed behind a chained wardrobe. The mattress is wrapped in cellophane, and only a sheet is placed on top, I have not seen there is a pillow on the bed or any blanket. He has no activity all day, he would like a book. He cannot move around and does not have a wheelchair, he moves around everywhere (in the bathroom and downstairs), since he arrived at this social care home he has not been out in the yard”, the CRJs report in the visit report.

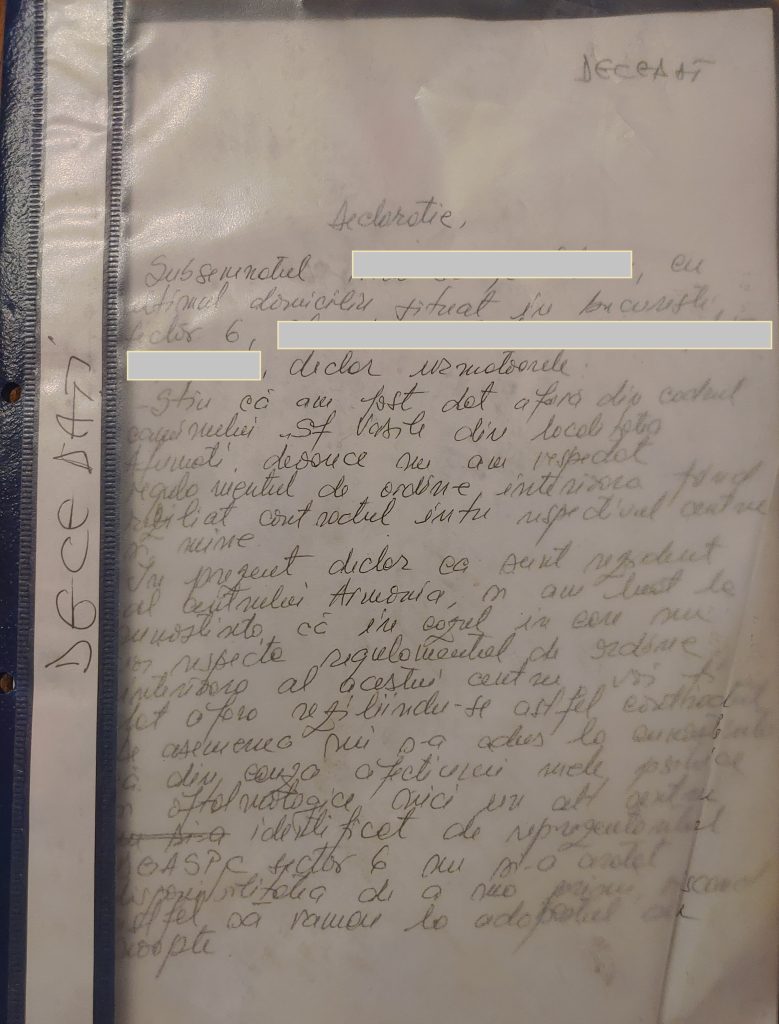

This beneficiary is not the only one who no longer wants to live here in these conditions. Several people are kept here against their will. The CRJ activists documented in detail the case of a woman who is the subject of a dispute between her two daughters: one, who remains in Romania, wants to take her mother’s house, while the other, who has emigrated to Italy, is trying to help her, by paying her lawyer, to leave this place and return to her home.

“Although she had informed the social care home’s employees that she no longer wished to live there, and the second daughter’s lawyer had notified the social care home that they had no grounds to keep the resident in the social care home against her will, the social care home’s representatives took no action to resolve the situation, maintaining the situation of deprivation of liberty without any grounds,” the CRJ team reports.

No one else on the outside is able to see in factual detail the nightmarish reality inside. People are locked inside, they can’t get out, even if accompanied – they wouldn’t have anyone to accompany them – and visitors can’t get in.

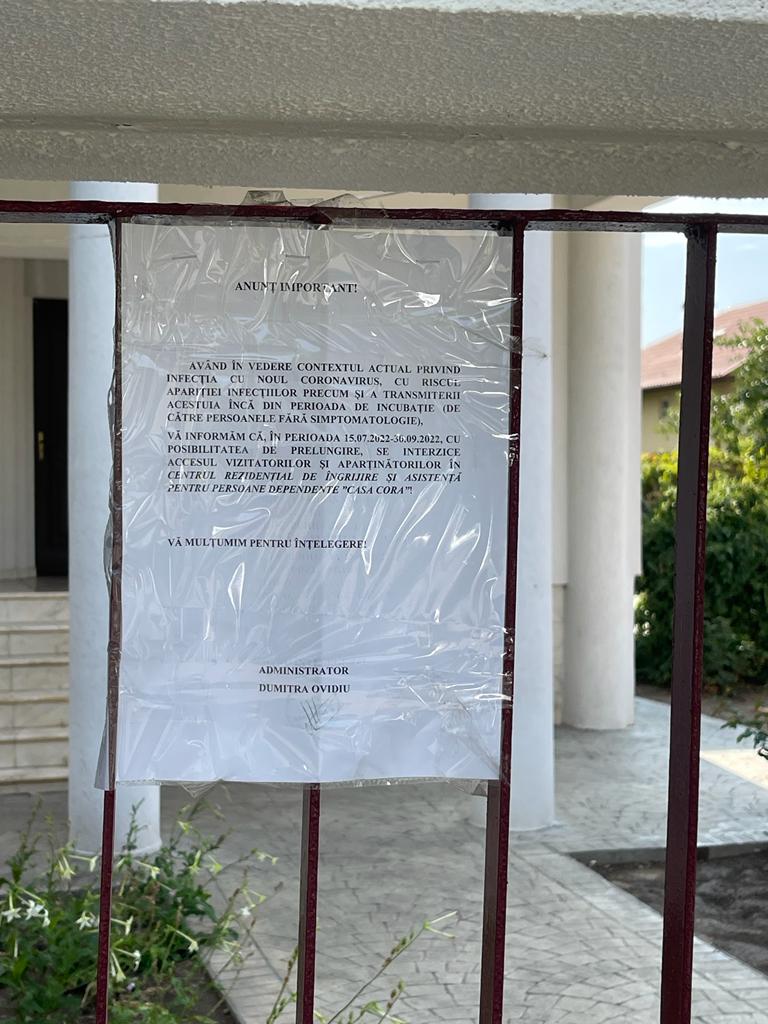

When CIM and Buletin de București reporters went to Casa Cora for the first time on the morning of 18 August 2022, there was a sign on the gate with the company’s administrator, Ovidiu Dumitra, Cristina Maria Dumitra’s husband, invoking the Covid-19 pandemic to ban visitors from entering. Until 30 September 2022, “with the possibility of extension”.

Epilog

Most likely, because it operates in the same paradigm as the ones before it, “Casa Cora” will also follow in the footsteps of the other spaces where Cristina Maria Dumitra’s money factories operated.

The woman who was found sleeping in the hallway during the first visit of the CRJ to Casa Cora, the bedridden one who was walking up and down the stairs to the bathroom or crawling up the stairs to the ground floor, sleeps in the same place, in the hallway. Except that the huge hallway was “shared”, until CRJ’s most recent visit in November, with a plastic wall of double-glazing.

“It’s very hard for me, I tell you. I still dream at night that I go to the gate and see them in the yard,” Elena, a former employee of Cristina Maria Dumitru’s centers, ends her long dialogue with reporters, sighing heavily.

Elena and Gina (obviously, the names are not the real ones, editor’s note) have also taken a beating from Dumitra’s boss, with whom they parted in a scandal.

The duped landlord Marius Sârbu had to tear down everything, down to the plaster, both in Gerbera and in Ștefănești. He threw away all the furniture, everything in the bathrooms, even the interior doors, complete with hinges. He spent thousands of lei on pest control alone.

Today, almost a year after Dumitra gave him his second stiffing, after many thousands of euros swallowed, the Gerbera house is open and has a new tenant. Not “social service providers”.

“I don’t need it as long as I live,” Sârbu throws out, obliquely.

We found Sârbu easy: he’s suing Dumitra to recover debts of tens of thousands of euros, as well as compensation for thousands and thousands more in work done to make the houses habitable again.

He fears he won’t have anything to take to cover his losses and is disappointed in the Romanian state.

A few minutes’ walk from the house he has left in ruins, in the new “social service” of Cristina Maria Mareș (formerly Widow, now Dumitra), people wither and die.

Reporters tried to contact Cristina Maria Dumitra to ask her questions about her business activities. We called her, but she asked us to write to her.

We sent her a few general questions about the centres she operated, but she surprised us with her answer: she basically offered to take on Gabriela Firea’s close associates who, under the umbrella of the St Gabriel the Brave Association, are her competitors in the business with addicts.

“Good evening and I have a lot to tell you about Mrs Firea’s centers there should be investigated not to me as they keep people on the street of pity without money.And I have not made 6 companies in 10 years, I think you confuse me”, Dumitra sent us by SMS, who then apologized that she can not talk to us now, but only on Monday, because she is “very cold”. Obviously, we kept the original spelling of the businesswoman’s message.

We asked Cristina Dumitra to facilitate a conversation with her husband, but he, she told us, is also ill.

“My husband is on antibiotics, he is much colder than I am because I was on vacation, do I really have to explain so much (sic!)”, Dumitra sent us, also by SMS.

At our insistence to have a quick chat on the phone, Cristina Maria Dumitra rebuked us, saying we were “harassing” her. She asked us to stop texting and offered to give us the number of her lawyer.

We also tried to speak to a certain Ioana Dragomir, the Dumitra’s “main man” in the social care home of “Casa Cora”. She could not answer any of our questions either, promising that she would quickly contact Cristina Maria Dumitra’s husband, the current company administrator.

No one contacted us.

SOURCE: https://www.investigatiimedia.ro/investigatii/lagarele-cristinei

SUMMARY and FULL REPORT available here: https://www.crj.ro/en/monitoring-report/