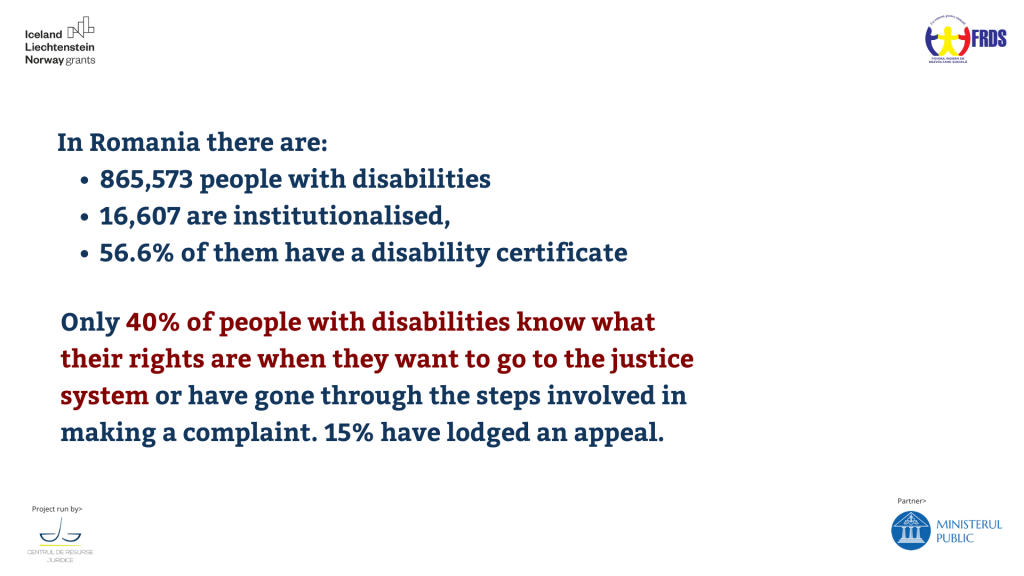

People with disabilities face multiple barriers when they need to access the justice system, many more and more subtle than those faced by people without disabilities. Whether they need to go through the legal process of reviewing court injunctions or need to report an injustice or violation of rights when they find themselves as victims or perpetrators – people with disabilities face a poorly prepared system that does not interact with them properly.

AdaptJust – accessible justice for people with disabilities is a project of the Centre for Legal Resources, in partnership with the Public Ministry, and benefits from a grant offered by Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway through EEA Grants under the Local Development Programme.

From November 2021 we aim to increase access to justice for people with intellectual and/or psychosocial disabilities. People with disabilities have less access to the justice system than people without disabilities when they need to complain about an injustice or rights violation. The removal of legislative and technical barriers becomes a necessary action in order for these people to have access to appropriate complaint and referral mechanisms to justice authorities. At the same time, staff in the justice system are not trained to understand the needs of people with disabilities. This makes them a vulnerable group in justice proceedings.

One and a half years after the project started, more than 350 people have been trained in the 15 courses organised in 34 counties, including about 100 magistrates, 70 psychiatrists and psychologists, 70 social workers. We also visited 10 psychiatric hospitals and social care institutions unannounced and worked with investigative journalists to bring to the attention of the public the violations of the rights of people with intellectual and/or psychosocial disabilities observed by us during monitoring visits.

We are developing a mobile app where people with disabilities confined in residential homes or hospitals can file complaints about abuse. In the Trainers of Trainers (ToT) courses, future trainers (lawyers, prosecutors, social workers, psychologists and psychiatrists) developed and tested a learning design that facilitates the understanding of concepts andthe exchange of experiences for the prevention of abuse of people with intellectual and psychosocial disabilities. Of the 30 participants, 15 were selected and are now AdaptJust courses trainers.

After each experience during the training sessions, the testimonies of the participants speak of the same need: to get to know each other better, to work together for a justice system accessible to people with intellectual and psychosocial disabilities.

Mrs Elisabeta Moldovan and Mrs Mariana Dumitrache are two people with different life experiences. Eli, as she likes to be called, was abandoned by her family at 6 weeks old. She lived 23 years in different institutions and then 10 years in the homes of different foundations. After more than 20 years of being locked up in an institution and suffering through countless abuses, the moment Eli arrived in the community she was confronted by the unfriendly justice system. Eli’s image of these people (police, lawyers, magistrates) was shrouded in many traumatic memories.

She is now self-employed, lives in an apartment and is co-president of Ceva de spus NGO and one of the core experts in the project team, attending training courses and doing double duty. She is an advocate for the rights of people with intellectual and/or psychosocial disabilities and works side by side with legal experts in monitoring and documenting how human rights are ensured in residential homes and psychiatric hospitals. As a monitoring expert, she has visited unannounced and written reports together with lawyers, psychologists and doctors.

In March 2022, Eli attended the course “Piloting Mechanisms to Protect the Rights of People with Institutionalized Disabilities“, where for three days he was in the same room with some of the people he once feared the most, justice professionals.

She had the opportunity to interact and work with two former prosecutors. One of them is Ms Mariana Dumitrache, a former prosecutor and today one of the trainers of the AdaptJust training courses.

In the interview below, Ms Mariana Dumitrache tells us about her experience with the barriers and preconceptions that exist on the other side, of the justice professionals and the work needed to dismantle them.

Ms Dumitrache attended the Training of Trainers (ToT) course organised by the CRJ in spring 2022 when, for the first time, she had the opportunity to get to know other perspectives, those of people with disabilities as well as psychologists and colleagues in the social protection system.

With more than 30 years of experience as a prosecutor at the prosecutor’s offices of the Iasi and Ploiesti Courts of Appeal and within the specialized structures, Ms. Mariana Dumitrache has carried out criminal prosecution and supervision of criminal prosecution, and has participated in court hearings and cases concerning the rights of disabled and vulnerable persons. In recent years she has worked as a volunteer and mentor within DGASPC Buzău for young people leaving the protection system.

We discussed with the prosecutor Mariana Dumitrache how her experience both in the training sessions and as a trainer, now, helps her to see the man behind the papers and reports that prosecutors receive when investigating a case where the person involved is one with intellectual and/or psychosocial disabilities.

***

I became a prosecutor and practiced for 30 years. From this position I met people with disabilities as victims and perpetrators of acts that were provided for by criminal law. At first these cases seemed simple to me, but because of the way they had to be dealt with in relation to the disabilities of the people involved, they became complex. I often had the impression that it was more difficult than in other situations to assess the evidence, to convince in the situation of such people that they were right, that they were sincere, that they were saying exactly what happened. Then we had to find ways of communicating that would make it easier for them to understand what happened to them. Sometimes it was very hard for me to tell when they were faking and when they were dissembling. That’s why I found this area very interesting.

In 2020 I stopped working as a prosecutor and volunteered with young people coming out of the protection system. That’s when I saw that it’s actually a much more complex equation: they have deep feelings, they can integrate into society if they are given the conditions they need…

At the invitation of a colleague, you signed up for the Training of Trainers course organised by the JRC in spring 2022. You told us beforehand that you said to yourself at the time that you were not going to try anything, that you took it all as a new experience, especially as you were already a volunteer and worked with people with disabilities in this way too.

That’s right. I found them interesting from the start, in that I would have the specialists very close to me. The exchange of information between the legal profession, the prosecuting profession and the other professions was now very close to me. I told myself that if I liked the format I would stay, if I didn’t.

And you stayed, and today you are one of the trainers in AdaptJust courses across the country.

Not only did I stay, but it seemed like an equation close to what perfect means. I met some very special people. I’ve never found medical language easier to understand. I had never in my profession been able to feel, on my own, what I understood after listening to social workers. Everything was all around me, but it was as if I had never seen it in that light.

What has helped you to see them in a different light now, after more than 30 years in the profession, during which you have met hundreds of people with disabilities? Had you had up to that point had some practical training in what disability means and what are its particularities and human manifestations?

I now found the medical language extremely easy to understand and found the practical usefulness extremely quickly. Because we as prosecutors, within the files, we found some documents containing many medical terms. When I was trying to get a picture I don’t think I always managed to do it very well, because no matter how hard I tried to understand the terms, when I was making the picture, the picture was still not very clear to me.

True, in college I had done a semester of forensics, with many, many aspects and tactics of listening to people, but there was little related to the specifics of a person with a disability. I had not, until the ToT (Training of Trainers) course, got to know them as people. That is probably why I was also impressed by the aspects presented by the social workers during the course. Because when I had come into contact with such people, I was strictly in a procedural framework, governed only by strict rules, and perhaps I did not always manage to get a complete picture of the person in question. With his life before, with what led him or what happened to him to end up being either a victim or a perpetrator.

I was educating myself about what the specifics of the person’s diagnosis meant and that took time. It would have helped if a professional, like a psychologist, had explained these things to me.

For example, if you had a case of a person with bipolar disorder, it would be helpful to talk to them rarely, repeat questions, not get too close, let them play with gum or hair, give them more time to think, and so on. Thus, when I received the diagnosis from the psychiatrist, I wouldn’t have taken three psychiatric treatises to research them, but I would have had there the doctor’s indications: he is prone to violence and the measure of hospitalization should be taken against him, in order to protect him and society, or on the contrary, let him free because it was only an episode compared to the challenge that was given to him, and absolutely nothing will happen.

If the social worker had also given me concrete data about the family (for example, if they are taking care of the person, or conversely, if they are concerned about selling their house), it would have been much easier for me to approach the case, in a much shorter time. This collaboration exists, however, only at institutional level, through officially drawn up reports.

Going back to the first courses organised by CRJ that you attended, the ToT courses in spring 2022. Where was the need felt most acutely, what profession did the prosecutor Mariana Dumitrache need to have contact with and better understand?

Without wanting to make a hierarchy, but without a doubt, the first thing is communication. So the psychologist, the psychiatrist are the closest. But in the same way, when a lawyer is part of the team and you find out how he is going to build his defence, it’s a plus of the criminal case that will be presented to the judge. Because I, as a prosecutor, will know exactly how to manage the issues so that the judge has a very clear picture of the case and can judge it in the best possible way.

It was the first time I saw colleagues from different professions and ages who, after two or three days together, formed teams and worked their asses off. That’s how I imagine the ideal, working in such interdisciplinary teams and in practice.

Another thing I have been left with since then that I had never imagined is the depth of the discussions on the different disabilities and how constructively one can see the integration of these people into society.

The criminal process has strict rules, but to my mind human interaction is indispensable to clarify all aspects of a case. In terms of people with disabilities we are talking about people who need special protection. Even when they are perpetrators, they did not end up in that situation by chance. I think that a team effort would be needed to take action as quickly as possible. The long paper trail creates some barriers to taking decisions when it is necessary to take them.

Does the man get lost in the paperwork?

I have a hard time admitting it, but I feel that to some extent I do.

Why don’t we look at people with disabilities as any other people?

I have asked myself this question many times. Sometimes I think we’re not schooled for it; sometimes I think it’s everyday experience. Current personal experiences take their toll. For a long time these people have not been around. There have been separate special schools; for a short time they have been part of society, sometimes with great effort. Psychiatric hospitals were not too close to the cities either.

You are now a trainer on AdaptJust courses. What motivated you to make this decision?

There comes a time in life when you really want the experience you’ve gained to make life easier for those who come after you. I enjoy it most when I am asked questions during my classes. To me this means that people not only listen, but also think about a particular professional problem they have encountered, or might encounter.

The course module that I support (Facilitating Access to Justice), is intended to create a dialogue between professions, in particular for participants from social professions to learn about the rigours of the criminal process and for legal professionals to learn about the avatars of people with disabilities should they have to participate in a trial.

Tell us a bit about the trainees, as you feel them not at the end of the three days, but on the first day. Are younger generations of professionals (prosecutors, judges, psychologists, psychiatrists, lawyers) more open about the right approach to disability?

This is my greatest joy as a trainer: seeing young people in the gym. I was nervous that they would leave. I have great joy when I see that it’s past their departure time and they are still there, still, still paying attention. I feel they are extremely interested and eager to learn as much as possible, they socialise in the breaks and try to learn more from each other and keep in touch. I feel they are interested both in the course and in knowing the other profession’s perspective and approach to these issues. I feel they are interested in treating these people with disabilities with all due respect and protection – the young ones. The other generations will also have to find the necessary openness. There comes an age when disability may simply come, even if it hasn’t from the start. A certain openness and a certain approach is appropriate at any age. Disability is not just related to birth, it can come at any time in a person’s life. And not only in one’s own life but also in the lives of loved ones or acquaintances.

How do you see yourself going forward, after the courses are over, applying both what you learned in the ToT sessions and from your interactions with participants?

Either I will attend such courses if I have the opportunity again, or as a volunteer as before. I used to volunteer for young people leaving the protection system. But still in the field of people with disabilities, because I gained enough experience and self-control.

I imagine we can all do well, provided we are good. Empathy is the first condition, beyond rules and law enforcement. Empathy makes the difference in the journey of the disabled person. If you manage in those moments to see him as a human being and give him all the chances at that moment, surely a very good solution will be embraced for him.